It’s not Trump’s fault. Hear me out on this one - we must blame a map.

There's a reason why geo-politics leads with 'geo'. Two decades before the outbreak of the Second World War, the impending end of the First World War was being foreshadowed by a huge clerical and cartographic burden: how to draw new international boundaries that would keep the peace, when it happened. The decisions made would eventually cast a long and oppressive shadow over Western Europe, and Adolf Hitler and the far right would goose-step into that darkness – but it was an American president who defined it: an American President, guided by his advisers of course.

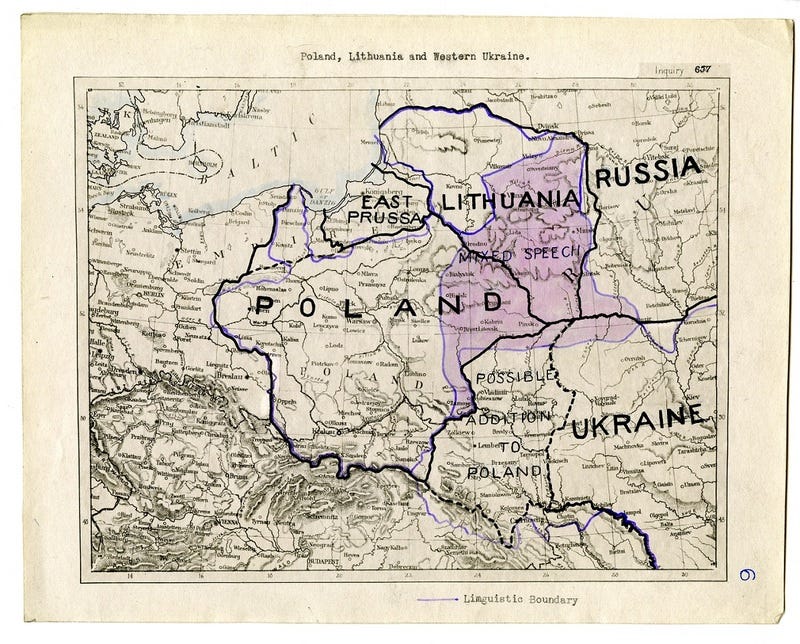

Triggered by the enduring moral turpitude, President Woodrow Wilson had commissioned a team of specialists to propose a scientific basis on which to define a forthcoming new, world order. The Economic and Social History of the World War became better known as ‘the Inquiry’, and new map-making featured heavily in that work. You know the Inquiry’s outcomes. You've seen them, even if you don't realise it.

The exercise was led by a great, worldly fool: Isiah Bowman, an American geopolitician who'd done a huge amount of work to vocalise the need for more world exploration and to reorganise and revitalise the American Geographical Society – but those were his few, good points. He was also a fierce antisemite. Still, having developed a reputation for expertise in settlement patterns over the years, it was Bowman who was asked to orchestrate mapping for the many reports and memoranda in the Inquiry.

It was Bowman who helped visualise the options for a peaceful, post-war Europe by exploring different ways to 'divvy up' the landscape - looking at ethnic mixes; the influence of language; the extent of agricultural and industrial regions; religious identities, road and rail networks... It was Bowman who defined a Polish state for an indisputably Polish population, and it was Bowman who helped determine the physical definition of the Weimar Republic. He has, since, been described as the man who “envisaged a global supervisory role for the United States.”

Starting to sound familiar? Déjà vu, perhaps?

Post war, it was Bowman who helped bring the US and UK together through his position – at the head of the table – in the Council of Foreign Relations (CFR). He was formative in shaping the very special Anglo-American relationship and it seems strange his name isn't known more widely outside PPE circles … but then, that is sometimes the nature of being a geopolitical driving force, or a special adviser at least. You get on with your job, steering a group of clap-happy passengers in a pre-determined direction. It's the conductor who makes all the noise: Presidents step easily into the role of frontman and ticket-collector - stating where they want to go comes easily. It's other people who make the wheels go round.

President 45-47, Donald J. Trump, is the conductor and Commander-in-Chief now sitting resolutely behind the big desk at rich.soup.noble (it's quite surreal, how what3words's algorithm makes apposite suggestions: The White House's official designation is engine.doors.club), and his driving ambition seems to be the rapid creation of a global legacy – more changes to the map of the world, writ large on the globe itself.

He's repeatedly referred to Canada as the 51st State. Trumpland, perhaps (there’s a President’s precedent for renaming states.) He's made outlandish overtures to Denmark, asking it to consider ceding Greenland. The Panama Canal is also on 47's hit-list — I’ll get to Panama mapping in WW2 in another stack — and he's just announced an imminent name change to the Gulf of Mexico . He really does want to run his pudgy finger under the three words, "Gulf of America". But is that even possible in peacetime? A name change of such substance to the world map? Yes, of course it is. We do it all the time.

The US Board on Geographic Names is responsible for upholding a gazetteer-approach to the use of place names across federal government, and Trump has a fair amount of sway there. The change will happen. We’ve seen similar changes, albeit domestic, and not batted an eyelid - mostly, they’re for a good reason. Obama, for example, gave the go-ahead for Mount McKinley to be renamed 'Denali' in 2015, which is how the Koyukon people had referred to it for centuries anyway; in 2003, George W. Bush authorised Squaw Peak in Phoenix, Arizona to be renamed Piestewa Peak to honour Lori Ann Piestewa, the first Native American woman to die in combat in the US military.

Still, when it comes to the 3,500+ miles of southern coastline bordered by more than one country, the International Hydrographic Organization will want to be involved in a rebrand, as will other international organisations, not least the UN's Group of Experts on Geographical Names. Public consultation would be good, too. However, to be fair to 47, there are at least two pragmatic reasons why he currently sounds like an ass with these proclamations.

First, the chances are, someone's briefing Trump with a Mercator projection. This is why we've got the Greenland Problem – seriously, cartographers refer to the unique, debilitating nature of Mercator’s projection as "the Greenland Problem". Kalaallit Nunaat gave rise to a scintillating exemplar of ways in which maps do not help in geopolitics: to the uninformed voyeur, the world's largest island appears to be more or less the same size as Africa, whereas Africa's land mass is actually fourteen times larger than Greenland.

We've all done it. Honey, I know it looks big to you from your perspective, but from over here? Sweetie. Puh-leese.

Second, Trump is merely following other Presidents' precedents. Couched as a NATO pact, the 1951 treaty between Denmark and the US gave America carte blanche to use it for military purposes - an agreement that replaced a similar accord made during the Second World War.

After the invasion and occupation of Denmark in 1940, the United Greenland Councils reiterated their oath of allegiance to King Christian in April 1941, but also made it very clear, GI Joe was welcome. It was agreed, "the Government of the United States of America shall have the right to construct, maintain and operate such landing fields, seaplane facilities, radio and meteorological installations as may be necessary for the accomplishment of the purposes set forth in Article II..." (helping Greenland to help itself) – and any one of these pesky accords leads to another geopolitical agreement. Arguably, I am over-simplifying this - but you know how it is.

What matters most perhaps, is that the subsequent NATO agreement wasn't an exclusive in any regard, irrespective of which map was used to make the arguments. Equal rights were granted to all other NATO members regarding Greenland. So if there's any strategy at all behind Trump's recent articulation to ‘get Greenland’, it's probably less to do with Inuit affairs, and more likely to do with that hyuuugely accessible land mass, just a couple of inches off the coast of Ellesemere Island, Canada - you can see that, right? On the map? Here, let me use this Sharpie… And then there’s Trump’s innate mistrust of other NATO members, of course.

You've really got to feel for the guy. Trump’s not the first President to map out grand ambitions in Canada’s direction, either.

As the son of a surveyor, cartographer, and land speculator on the Virginia frontier, Thomas Jefferson already knew a thing or two about setting out to put America’s stamp on the map. During his presidency, the Louisiana Territory was acquired from France. He sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition up the Missouri River in 1803, too: these were both contributing factors to his aspiration for, in his words, helping establish “an empire for liberty”.

But it was in 1812, while he was acting as a special adviser to the current president, James Madison, that Jefferson started boasting “the acquisition of Canada… will be a mere matter of marching.” Seems to me, Jefferson hadn't studied the topographic reality of the Canadian hinterland very well. Then again, he’d got form in the ‘land and legacy’ department, too.

Thomas Jefferson had already proposed ten new names to help define the immense triangle of land between the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers: Illinoia, Michigania, Saratoga, Washingon, Chersonesus, Sylvania, Assenisipia, Metropotamia, Polypotamia, and Pelisipia.

… except, he didn’t. The Continental Congress had been commissioned to impose law and order north and west of the Ohio River; the first legislative effort had been made effective through the Land Ordinance of 1784; and there were hundreds and hundreds of counsellors involved, all poring over (badly drawn) cartography. More specialist advisers, more worldly fools.

As we see endless journalistic viewpoints on 47’s statements of intent over the coming weeks, it’s worth remembering that Presidents are not the lone spark, igniting geopolitical unease. There are always advisers in the background, and at some point, yes, they are all using a map to fan the flames.

Just joined your substack yesterday, enjoyed the first article immensely.

That was most enlightening. Thank you!