Today, V is For Valentin.

Bremen’s U-Boat Bunker - should it be on our battlefield tour, or not?

A submarine pen in Bremen was not, technically, our priority. Der U-Boot-Bunker was an addendum, added into a recce with the casual air of an afterthought – a coda to the business of planning stands and sit-downs for Walking with The Jocks, our battlefield tour slated for October.

Meticulously mapped, naturally, at the moment our itinerary is focused on following the 52nd (Lowland) Division during the final spasms of the war in North West Germany. Running up from the Dortmund–Ems Canal through the Teutoburger Wald, skirting the margins of Ibbenbüren, we then travel on to Bremen, a city in which RAF Bomber Command insisted on being deeply involved with the ongoing evolution of Hanseatic civic architecture.

The tour also includes Rethem, Gross Eilsdorf and other locations besides; criss-crossing the Rive Aller many times, with the camps at Sandbostel and Bergen-Belsen, and Lüneburg Heath also in the plan – names freighted with moral weight, where the landscape discloses what liberation uncovered.

However, there we were, and Valentin was nearby. Traffic was less than ideal, but as the weather was bizarrely luminous - a sunny disposition owing nothing to history - we gave ourselves permission to make a detour.

It’s always a challenge when you’re putting these things together. Nobody is a sage; no one offers the perfect itinerary; everybody has their own area of expertise, and there’s always something you (or we), want to see, but time is an enemy, and boot-leather is precious. So what do you put in, and why? Who do you leave out, and when? Which stories are must-haves; which stands are essential; how far off the beaten track can you take your guests before that path becomes a direct route to exposing your obsessive curiosity, rather than a unique and fascinating diversion for them?

For Andy and me, it’s incredibly important that ‘Walking With the Jocks’ does stay focused on Peter White and the 4th Battalion, KOSB’s war in Europe. That can be a challenge when there’s so much going on. On this recce though, we knew that a quick detour to Farge, north of Bremen, would provide an answer to the question that had been bugging us for a while.

If it’s sub-marine not army… if it’s Peter-adjacent but not Peter-central… if it’s very definitely part of the Bremen story, is Valentin in, or out?

Sometimes called U-Boot-Bunker Farge, the Valentin bunker lies on the north bank of the Weser, at the outer edge of Farge. Bremen-Farge. The terms are interchangeable, though pedantry insists on the distinction that Valentin is the bunker and Farge is the suburb – a district of Bremen that bleeds into the municipality of Schwanewede. The municipal road-sign replacement team does not believe in consistency, and duality has persisted for decades. So too do inevitable superlatives, which bubble up like the prose of a breathless Discovery Channel script: the largest surviving U-boat bunker in Germany; an astonishing edifice; Concrete. Overkill. Engineering as metaphysics. A Nazi megastructure, of course.

We weren’t completely naïve; we did know something about it being a case study in ambition. But if we went to understand its relevance, then we left with something far heavier. An understanding of weight: not of tonnage, but of burden. Valentin is a reminder of the Allies’ purpose - liberation.

To call it a megastructure is to understate its existence by a country mile, and then some. It is the largest free-standing bunker in Germany, with a footprint that runs to some 35,000 square metres – a monument not to success, but to insistence. The outer shell measures over 400 metres in length and is almost 100 metres wide.

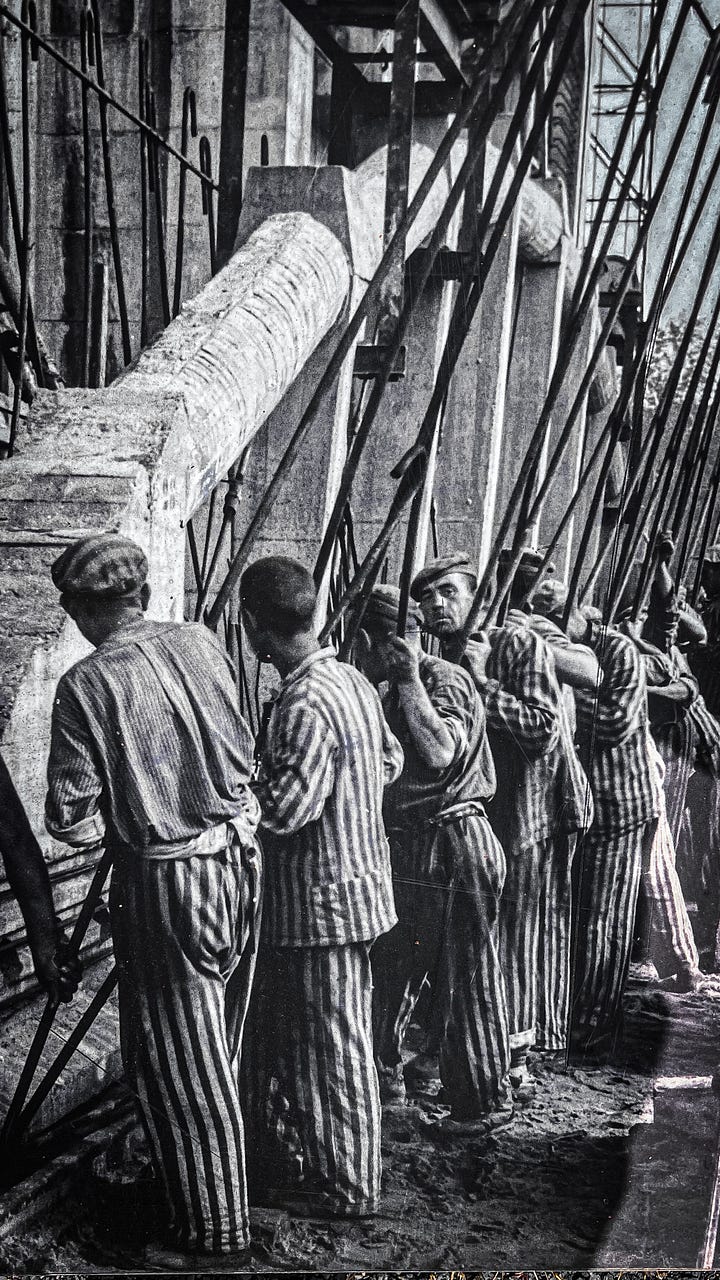

“Suddenly, the monster looms on the north side, more than 30 metres high and five football fields long. A shiver involuntarily runs down our spines (...). We can sense that the monster is as terrifying as the gullet of a wild beast. We are here in the hundreds, ready to be devoured by it, by the rain, by the cold (…). We have no difficulty imagining this mass of concrete and iron to be our grave.”

Pierre Saufrignon, France, former concentration camp prisoner

From a distance, even though it has been softened by decades of lichen and salt, its silhouette dominates the landscape: a squat, obdurate monolith that rises abruptly from urban sprawl; thick-walled and mute. Without windows, without welcome. There’s no reverberating hum of air conditioning units; no percussive anvil ringing out from within. The grounds, such as they are now, are devoid of the intrusive techno-jiggery that so-often insists visitors take a pre-defined route through a memorial at scale; instead, the site is sensitively made easier to understand through low-key, low-level information panels. A quote; a comment; a picture – people and their stories taking priority over statements agreed by culturally-aware committees. A breath of fresh air.

That fresh air is apparent without and within: the roof – the bunker’s boast – was designed to be over seven metres thick in places, and built with stratified ferro-concrete that should have deflected the attention of Allied bombers. That construction pushed wartime engineering to its limits: flood mitigation, deep foundations, prefabricated components. Nothing was improvised, and yet Valentin never functioned. In March 1945, it met its end not through occupation or liberation, but through intrusion: a squadron of RAF Lancasters delivered Barnes Wallis’s Grand Slam and Tallboy bombs, cracking open the roof, and compromising the building’s integrity. The damage was irreversible. Valentin was rendered useless, a cathedral of concrete never consecrated by the submarines it was designed to build. The war was already lost.

We got out of the car, expecting to appreciate its scale. And we did, but not in the way we’d imagined. Instead of indulging the bunker’s architectural gravity, the curators of the memorial site have taken another path. The concrete is overwhelming, of course – a hypertrophic assertion of function over form. But it has been allowed to do something alien to Nazi architecture: it has been allowed to age. And not just to age gracefully but to crack, and to fragment, and to lose face completely. The bunker has not been restored, reimagined, or reanimated. There is no cosmetic infill. No poetic lighting. No didactic reconstructions to ameliorate fly-by coach party experiences, or to soften its imposition. What was poured in totalitarian urgency now sits in a state of honest erosion. Yes, the Health and Safety Gnomes are in evidence on one side of the main hall – less a room, more a continent; the light is minimal and deliberately so - but not on the other. There, danger is imminent.

“When I came to Bremen-Farge in January of 1943, there was an enormous construction pit there. The water was being continuously pumped into the river Weser. We had to haul huge pillars into the pit on our backs and ram them into the ground. That was the hardest job, carrying the pillars. After the steel skeleton was complete, we filled the walls with concrete. (...).”

Nikolaj Grigorevic Zhuk, Ukraine, former concentration camp prisoner

Once inside the bunker, you are free to roam. No natural daylight dilutes the enormity of the space. Instead, you get depth, volume, and acoustic infinity. The hall, divided into two parts, is an exercise in calibrated monotony broken by scars in the roof and a wide, flat wall that has been repurposed as a screen. A real one. On it plays a looped video – projected in theatrical resolution, and with quiet persistence. It spans nearly 20 metres across two walls. It does not demand attention. It waits for it.

If you stop to watch and listen, as we did, and to let the bunker’s darkness truly settle in, the effect is extraordinary. The acoustics are cathedralic. The memories of men who helped build this edifice, echo and rebound from the walls; each word arrives a second or two after the subtitles appear, and each one is none the less impressive because of it.

Beyond the main hall, the concrete has been allowed to age, and to fragment. What we found was not an exposition of engineering, but of suffering. Valentin was built not by Bremen’s finest engineers or patriotic volunteers in pressed field-grey, but by prisoners, working around the clock. Thousands of prisoners, not as a contribution to the war effort but as the war effort – the expendable margin on which the Reich balanced its industrial desperation.

Between 1943 and 1945, more than 10,000 forced labourers were fed into the machinery of Valentin’s construction. The workforce came from every corner of occupied Europe: Soviet POWs, Polish civilians, Dutch political prisoners, Italian internees, Jews, and German dissidents, all housed in satellite camps – Farge, Neuenkirchen, and Schwanewede – which made them invisible to anyone who didn’t wish to see them. The largest camp, KZ Farge, operated as a subcamp of Neuengamme, and by the spring of 1945 held over 2,000 men in a facility designed for half that number.

They laboured in 12-hour shifts, day and night, exposed to wind, rain, concrete dust, and the casual brutality of SS guards and Organisation Todt foremen. Many were beaten. Many starved. Some were crushed in concrete-pouring accidents or collapsed under beams. Disease was rampant. Sanitation was theoretical, food was not. It simply wasn’t there. By conservative counts, 1,600 workers died ; 553 French prisoners were confirmed as having lost their lives during the construction – other estimates, depending on the radius of culpability, put the number much closer to 6,000. Bodies were burned or buried in shallow graves. Few were named. Most were filed away as quantities.

The memorial to slave labour is austere. As it should be. No audio guides hissing behind you; no digital dioramas on the blink. No mannequins or artificial textures. Just the bunker, and a path through the evidence. One panel outlines the SS command hierarchy for the labour camps surrounding the site. Another lists the diseases logged by camp doctors in spring 1944: dysentery, typhus, pneumonia, starvation. A fragment of clothing, a register, a roll-call sheet with red ticks beside the dead. A photograph of sunken eyes, the captions are unflinching. There is no emotional baiting, no manipulative crescendo. The horror lies in ordinary detail. The measurements of calorie rations, and the notation codes for discipline. Arbeitsunfähig – zu entfernen – ‘unfit for work, to be removed’ - is scrawled beside dozens of names.

“Terrible wasn’t the lack of food, terrible wasn’t having to work, terrible wasn’t getting up early. Terrible was the extent of the unnecessary suffering! Suffering which murdered the feeling that you were human. That is the cruellest, most monstrous thing about it!”

Raymond Portefaix, France, former concentration camp prisoner

On 27 March 1945, 20 Avro Lancaster bombers took off from RAF Woodhall Spa, modified to carry Tallboys, and Grand Slams – the largest conventional bombs dropped to that point; designed to penetrate deep into hardened structures before exploding, tasked with rendering the bunker unusable.

![r/HistoryPorn - An RAF officer inspects the hole left by a 'Grand Slam' bomb penetrated German submarine pens at Farge, north of Bremen, Germany. 27 March 1945, [800x547] r/HistoryPorn - An RAF officer inspects the hole left by a 'Grand Slam' bomb penetrated German submarine pens at Farge, north of Bremen, Germany. 27 March 1945, [800x547]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8bb076d1-f7d8-4d0a-9f0b-e380a7acb662_640x437.jpeg)

The impact was surgical. The concrete was not pulverised; its integrity was undermined. Grand Slams punched through the roof, detonating inside and shaking the structure apart from within. One slab of ceiling, weighing hundreds of tonnes, was lifted off its bearings. Vaulted arches cracked, and the foundations shifted – Valentin had taken years to build, but it took the RAF minutes to make it pointless.

In early April 1945, as the Allied forces approached Bremen, the SS began evacuating KZ Farge and other subcamps around the region. Prisoners were forced to march north and east. Death marches - anyone who collapsed was shot. Survivors spoke of walking skeletons, of frostbitten feet and roadside corpses. Some of those prisoners were sent to Stalag X-B Sandbostel, a large POW and detention camp that, by April, had become a vast and overcrowded holding site for evacuees from Neuengamme and its subcamps; others were sent to Belsen. Two end points in a dismal geography of dispersal, and at this point, I’m making no apology for digressing away from the customary maps.

From 1960 onwards, the West German Navy maintained a materials depot in the building. As the Cold War wore on, the bunker was taken off maps. For decades, there was no commemoration of the slave labour programme or the victims of the bunker’s construction. When the Navy left in December 2010, the incoming team made a point - expanding their remit to include not only commemoration, but also research into the history of bunker construction, the camps, and especially the forced labourers, POWs, concentration camp inmates, and police detainees. Today, they still work on documents collected over the decades, now housed in the memorial site's archive.

Perhaps the most important holding on site is that of the Arolsen Archives , formerly the "International Tracing Service of the Red Cross." Hundreds of thousands of documents relating to victims of Nazi crimes are stored here, including the inpatient register of the Farge subcamp's infirmary. More than 80 years after construction began, new findings are still coming to light.

In October 2025, when we go ‘Walking With the Jocks’ in October, we’re not just following in the footsteps of the 52nd (Lowland) Division. There’s more to the men’s achievements than ‘head for Bremen.’ We’re tracing an exposure of systems, of cruelty, and of liberation too - how it’s remembered by those who were not there, but owe their lives to those who were. Sandbostel and Belsen show us the meaning of endurance, because Valentin shows us the enormity of the Reich’s enduring futility.

Yes, if it’s humanly possible, all three locations are on the list.

This isn’t a shameless plug, it’s an invitation. Join us on tour in October. Drop me an email or find out more at walkingwiththejocks.co.uk, or book yourself in direct with Battle Honours, who are the brilliant, brilliant team handling all our tour administration. It’s 5 days. You won’t forget it.

First class Merryn. Reminds me of my visits to Wiezernes and Eperlecques (Watten), both connected to the V2 program. Similar waste of lives and resources. Rendered useless, utterly useless, by the USAAF and RAF ops with TALLBOYs.